from American Journal of Clinical Pathology

Is Incidentally Detected Prostate Cancer in Patients Undergoing Radical Cystoprostatectomy Clinically Significant?

Roberta Mazzucchelli, MD, PhD; Francesca Barbisan, MD; Marina Scarpelli, MD; Antonio Lopez-Beltran, MD, PhD; Theodorus H. van der Kwast, MD, PhD; Liang Cheng, MD; Rodolfo Montironi, MD, FRCPath

Published: 08/21/2009

Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Cystoprostatectomy specimens obtained from patients with bladder cancer provide a unique opportunity to assess the features of silent prostate adenocarcinoma (PCa). The whole-mount prostate sections of 248 totally embedded and consecutively examined radical cystoprostatectomy (RCP) specimens were reviewed to determine the incidence and features of incidentally detected PCa. PCa was considered clinically significant if any of the following criteria were present: total tumor volume, 0.5 cc or more; Gleason grade, 4 or more; extraprostatic extension; seminal vesicle invasion; lymph node metastasis (of PCa); or positive surgical margins. PCa was present in 123 (49.6%) of 248 specimens. Features were as follows: acinar adenocarcinoma, 123 (100.0%); peripheral zone location, 98 (79.7%); pT2a, 96 (78.0%); pT2b, 11 (8.9%); pT2c, 9 (7.3%); pT3a, 5 (4.1%); pT3b, 2 (1.6%); pT4, 0 (0.0%); Gleason score 6 or less, 107 (87.0%); negative margins, 119 (96.7%); pN0 for PCa, 123 (100.0%); and tumor volume less than 0.5 cc, 116 (94.3%). Of the 123 incidentally detected cases of PCa, 100 (81.3%) were considered clinically insignificant. Incidentally detected PCa is frequently observed in RCP. The majority are clinically insignificant.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) can be found incidentally when the prostate is removed during cystoprostatectomy for bladder cancer (incidentally detected cancer), found latently at autopsy without ever having caused symptoms during the person’s lifetime, or clinically diagnosed by physical examination, laboratory tests, and/or symptoms. The incidence of prostate cancer in each of these settings is different.[1-4]

It is widely known that PCa has great discrepancy between its high incidence and its comparatively low morbidity and mortality rates.[5,6] For example, the lifetime probability of being diagnosed with PCa is 16% and the probability of dying of PCa is 3%.[5] Early diagnosis of lethal prostate cancer is a laudable goal, as is avoidance of unnecessary treatment, but current methods are inaccurate for making this determination. In no other malignancy is there such a vast reservoir of undetected cases that may never become clinically significant or cause death,[7] yet we are unable to stratify significant and insignificant cancers.

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence and features of incidental PCa in radical cystoprostatectomy (RCP) specimens for bladder cancer.

Materials and Methods

The study was done on specimens from 248 consecutive men with muscle-invasive bladder urothelial carcinoma and no history or clinical evidence of PCa before surgery and whose RCP specimen was examined from 1995 to 2007 at the 5 pathology services associated with the United Hospitals-Polytechnic University of the Marche Region, Ancona, Italy. The mean patient age was 68 years (range, 43–95 years). All patients were white men from the Marche Region, located in eastern central Italy, where a relatively homogeneous population lives. The procedure for this research project conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

A routine pathologic examination was used for all RCP specimens. Soon after the operation, the prostate was severed from the bladder and then covered with India ink. After fixation for 24 hours in 4% neutral buffered formalin, the prostate specimens were step sectioned at 3-mm intervals perpendicular to the long axis (apical-basal) of the gland (in the years 1995 and 1998, some of the prostate specimens were sliced at an interval of 5 mm).[1] The apex, base, and seminal vesicles were removed from each specimen and submitted in total for routine histologic examination. The cut specimens were postfixed for an additional 24 hours and then dehydrated in graded alcohols, cleared in xylene, embedded in paraffin, and examined histologically as 5-µm-thick, whole-mount, H&E-stained sections.[8,9]

All of the prostate H&E-stained slides and pathology reports were reviewed by 2 genitourinary pathologists (R. Mazzucchelli and R. Montironi). Data on the features listed in Table 1 were obtained. The stage of prostate cancers was based on the 2002 revision of the TNM.[10] The Gleason grading used in this study was the modified system according to the International Society of Urological Pathology/World Health Organization.[11,12]

Table 1. Incidentally Detected Prostate Cancer

PCa volume was determined by using the point-counting method as previously described.[13] Briefly, the number of grid points falling within the area with cancer were counted, multiplied by the area associated with each point (2.25 mm2), then multiplied by the thickness of the slice to yield the volume of cancer in the corresponding prostate tissue slice. The volume obtained in all slices was then summed and multiplied by a shrinking factor of 1.3.

For the present study, PCa was considered clinically significant if any of the following criteria were present: total tumor volume, 0.5 cc or less; Gleason grade, 4 or more; extraprostatic extension; seminal vesicle invasion; lymph node metastasis (of PCa); or positive surgical margins.[14]

Results

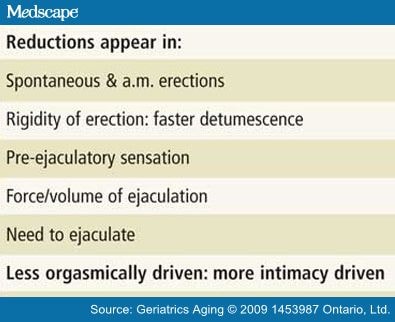

PCa was present in 123 (49.6%) of 248 specimens (Table 1). The mean patient age was 67 years (range, 53–95 years). All were acinar adenocarcinomas, and 98 (79.7%) were located in the peripheral zone (Figure 1). Of the 123 adenocarcinomas, 96 (78.0%) were pT2a, whereas 11 (8.9%) and 9 (7.3%) were pT2b and pT2c, respectively, with lower frequency in other pT categories ( Table 1 ). In 107 specimens (87.0%), the Gleason score was 6 or less. Negative margins were present in 96.7% of cases. All cases were pN0 for PCa. In 116 specimens (94.3%), the volume was less than 0.5 cc. Of the 123 cases of incidentally detected prostate cancer, 100 (81.3%) were considered clinically insignificant. Follow-up data were available for 60 patients (length of follow-up, mean, 60 months; range, 1–120 months). The cause of death was not related to the PCa in any of the patients.

Table 1. Incidentally Detected Prostate Cancer

Table 1. Incidentally Detected Prostate Cancer

Figure 1. Whole Mount Section With Monofocal Cancer (Dotted Area) Located in the Peripheral Zone (H&E, ×1).

Discussion

The frequency of PCa incidentally detected in RCP specimens is extremely variable, ranging from less than 10% to nearly 60%.[15,16] This variability can be explained by several factors, including pathologic sampling techniques. In this respect, the slice thickness of the prostate and whether the prostate is totally embedded represent 2 important issues. In our study, with slices taken every 3 mm from the base to the apex of the gland, as is usually performed for radical prostatectomy specimens, incidentally detected PCa was present in 49.6% of specimens. Others observed similar rates of PCa using the same technique.[17-21] Ruffion et al[22] found a 51.0% rate of incidentally detected PCa, advocating the use of even finer slices (2.5 mm). Similar results were seen in the study by Abbas et al,[23] who examined prostatic tissue from 40 RCP specimens with serial step slices taken at 2- to 3-mm intervals. The frequency of autopsy-detected cancer is similar.[1] On the other hand, a lower incidence was seen in studies using a different pathologic examination protocol. For example, Moutzouris et al[24] identified PCa in 27% of the examined specimens when using 5-mm thick slices, while the percentage was low (4.0%) in a report from a Taiwanese group.[25] The latter result could be due to the influence of the study population in addition to the pathologic technique, as it is well known that the incidence of PCa is higher in the West than in Asian countries.[26]

In 81.3% of the incidentally detected carcinomas in the present study, the total tumor volume was less than 0.5 cc, and, in this group, there were no tumors with a Gleason pattern of 4 or greater, extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle invasion, lymph node metastasis (of PCa), or a positive prostatic surgical margin. This means that the majority of incidentally detected cancers can be considered clinically insignificant, ie, only 18.7% of incidentally detected cancers in our series were clinically significant.

The proportion of clinically significant cancers in the series published previously varies from 10% to 70%[8,17-25,27-39] Table 2 . Also such wide variability could be related to the pathologic examination protocol, criteria adopted to define clinically significant cancer, and the population under investigation. Prange et al[33] found PCa incidentally in 48% of their cases, and only 10% of the tumors were clinically significant, whereas the presence of clinically significant PCa in the study by Abdelhady et al[27] was 31%. Revelo et al[20] found a 41.3% rate of unsuspected PCa; 48% of these were considered clinically significant. In a series of 141 RCPs reported by Delongchamps et al,[29] 20 (14.2%) PCas were identified, 14 of which (70%) were considered significant.

Table 2. Prostate Cancer in Radical Cystoprostatectomy Specimens: Data From the Literature*

Androulakakis et al[40] suggested that the simultaneous finding of PCa and bladder cancer did not affect the prognosis of either disease. The patient’s prognosis seemed to be related to the characteristics of each tumor, separately.[40] Pritchett et al[34] reported no worse survival in patients with both cancers compared with patients with bladder cancer alone. In our study, in none of the patients whose follow-up data were available to us was the cause of death related to the PCa. Other authors have found results similar to ours.[23,24,29,32,41]

In the series reported by Delongchamps et al,[29] 10 patients died of bladder cancer after a median interval of 13 months. Eight patients remained free of disease after a median follow-up of 64.5 months. The poor survival rate was due to the advanced stage of the bladder tumors seen in the majority of patients, compared with that of the incidentally detected PCa.[29] In the study by Abbas et al,[23] 16 of 18 patients with incidentally detected PCa were alive with no apparent disease progression at a mean follow-up of 15.2 months. The cause of death in the 2 patients who died was not related to the PCa.[23] Moutzouris et al,[24] in analyzing patient outcomes for 16 patients with unsuspected PCa, found only 1 recurrent prostatic disease. Concomitant PCa was localized to the apex and recurred on a urethral-ileal anastomosis. At a mean follow-up of 39 months, 7 patients died of metastatic bladder cancer, whereas the patient with recurrent PCa was still alive.[24]

Compared with the aforementioned studies, in the present investigation, precise information on clinically insignificant cancer was obtained from a relatively homogeneous population in eastern central Italy and from a population larger than in the other series, by meticulous pathologic grading and staging after review, and by volume measurement with sectioning at an interval of 3 mm. A detailed examination of prostatic tissue specimens was of paramount importance in the detection of small cancers.

Previous studies from our group indicated that incidentally detected PCa is less aggressive than PCa clinically detected with regard to stage, Gleason score, and surgical margin status.[1] The expression of some markers of aggressiveness (ie, nuclear and nucleolar size, proliferation activity, HER2 gene amplification, HER2 protein expression, endothelin-1 and its receptors, and racemase) was investigated by our group in incidentally detected pT2 Gleason score 6 PCa and compared with clinical cancer with matched stage and score. It was found that incidentally detected cancers are different from clinically detected cancers in terms of marker expression, having cell features of less aggressiveness.[1-4] To the best of our knowledge, studies comparing insignificant with significant incidentally detected cancer are lacking.

Incidentally detected PCa is frequently observed in RCP specimens. The majority are considered clinically insignificant. The results of the current investigation could be of paramount importance when trying to understand the type of cancers found in screening programs. To this end, it would be of great interest to conduct a study in which the features of incidentally detected PCa are compared with those of PCa found in a screening program. Such a study could be of help in further defining the criteria for clinically insignificant prostate cancer.

References

Montironi R, Mazzucchelli R, Santinelli A, et al. Incidentally detected prostate cancer in cystoprostatectomies: pathological and morphometric comparison with clinically detected cancer in totally embedded specimens. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:646-654.

Montironi R, Mazzucchelli R, Barbisan F, et al. HER2 expression and gene amplification in pT2a Gleason score 6 prostate cancer incidentally detected in cystoprostatectomies: comparison with clinically detected androgen-dependent and androgen-independent Cancer. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1137-1144.

Santinelli A, Mazzucchelli R, Barbisan F, et al. á-Methylacyl coenzyme A racemase, Ki-67, and topoisomerase IIá in cystoprostatectomies with incidental prostate Cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:657-666.

Barbisan F, Mazzucchelli R, Santinelli A, et al. Overexpression of ELAV-like protein HuR is associated with increased COX-2 expression in atrophy, high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, and incidental prostate cancer in cystoprostatectomies [published online ahead of print April 30, 2008]. Eur Urol.

Hayat MJ, Howlader N, Reichman ME, et al. Cancer statistics, trends, and multiple primary cancer analyses from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Oncologist. 2007;12:20-37.

Breslow N, Chan CW, Dhom G, et al. Latent carcinoma of prostate at autopsy in seven areas. The International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France. Int Cancer. 1977;20:680-688.

Stamey TA, Freiha FS, McNeal JE, et al. Localized prostate cancer: relationship of tumor volume to clinical significance for treatment of prostate Cancer. Cancer. 1993;71:933-938.

Esgueva R, Lorente JA, Mojal S, et al. Incidental prostatic adenocarcinoma in radical cystoprostatectomy specimens: the impact of embedding protocols [abstract]. Mod Pathol. 2008; 21(suppl 1):155A.

Montironi R, Mazzucchelli R, van der Kwast T. Morphological assessment of radical prostatectomy specimens: a protocol with clinical relevance. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:211-217.

Sobin LH, Wittekind C. Urologic tumours: prostate. In: Sobin LH, Wittekind C; for the International Union Against Cancer (UICC), eds. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 6th ed. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss; 2002:184-187.

Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC Jr, Amin MB, et al; ISUP Grading Committee. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1228-1242.

Lopez-Beltran A, Mikuz G, Luque RJ, et al. Current practice of Gleason grading of prostate carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2006;448:111-118.

Scattoni V, Montironi R, Mazzucchelli R, et al. Pathological changes of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostate cancer after monotherapy with bicalutamide 150 mg. BJU Int. 2006;98:54-58.

Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Carmichael M, et al. Pathologic and clinical findings to predict tumor extent of nonpalpable (stage T1c) prostate Cancer. JAMA. 1994;271:368-374.

Autorino R, Di Lorenzo G, Damiano R, et al. Pathology of the prostate in radical cystectomy specimens: a critical review [published online ahead of print August 28, 2008]. Surg Oncol. In press.

Damiano R, Di Lorenzo G, Cantiello F, et al. Clinicopathologic features of prostate adenocarcinoma incidentally discovered at the time of radical cystectomy: an evidence-based analysis. Eur Urol. 2007;52:648-657.

Cindolo L, Benincasa G, Autorino R, et al. Prevalence of silent prostatic adenocarcinoma in 165 patients undergone cystoprostatectomy: a retrospective study. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:269-271.

Conrad S, Hautmann SH, Henke RP, et al. Detection and characterization of early prostate cancer by six systematic biopsies and fine needle aspiration cytology in prostates from bladder cancer patients. Eur Urol. 2001;39(suppl 4):25-29.

Montie JE, Wood DP Jr, Pontes JE, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate in cystoprostatectomy specimens removed for bladder Cancer. Cancer. 1989;63:381-385.

Revelo MP, Cookson MS, Chang SS, et al. Incidence and location of prostate and urothelial carcinoma in prostates from cystoprostatectomies: implications for possible apical sparing surgery. J Urol. 2004;171:646-651.

Yang CR, Ou YC, Ho HC, et al. Unsuspected prostate carcinoma and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasm in Taiwanese patients undergoing cystoprostatectomy. Mol Urol. 1999;3:33-39.

Ruffion A, Manel A, Massoud W, et al. Preservation of prostate during radical cystectomy: evaluation of prevalence of prostate cancer associated with bladder Cancer. Urology. 2005;65:703-707.

Abbas F, Hochberg D, Civantos F, et al. Incidental prostatic adenocarcinoma in patients undergoing radical cystoprostatectomy for bladder Cancer. Eur Urol. 1996;30:322-326.

Moutzouris G, Barbatis C, Plastiras D, et al. Incidence and histological findings of unsuspected prostatic adenocarcinoma in radical cystoprostatectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1999;33:27-30.

Lee SH, Chang PL, Chen SM, et al. Synchronous primary carcinomas of the bladder and prostate. Asian J Androl. 2006;8:357-359.

Hsing AW, Tsao L, Devesa SS. International trends and patterns of prostate cancer incidence and mortality. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:60-67.

Abdelhady M, Abusamra A, Pautler SE, et al. Clinically significant prostate cancer found incidentally in radical cystoprostatectomy specimens. BJU Int. 2007;99:326-329.

Aydin O, Cosar EF, Varinli S, et al. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in prostate specimens: frequency, significance and relationship to the sampling of the specimen (a retrospective study of 121 cases). Int Urol Nephrol. 1999;31:687-697.

Delongchamps NB, Mao K, Theng H, et al. Outcome of patients with fortuitous prostate cancer after radical cystoprostatectomy for bladder Cancer. Eur Urol. 2005;48:946-950.

Hosseini SY, Danesh AK, Parvin M, et al. Incidental prostatic adenocarcinoma in patients with PSA less than 4 ng/mL undergoing radical cystoprostatectomy for bladder cancer in Iranian men. Int Braz J Urol. 2007;33:167-173.

Kabalin JN, McNeal JE, Price HM, et al. Unsuspected adenocarcinoma of the prostate in patients undergoing cystoprostatectomy for other causes: incidence, histology and morphometric observations. J Urol. 1989;141:1091-1094.

Kouriefs C, Fazili T, Masood S, et al. Incidentally detected prostate cancer in cystoprostatectomy specimens. Urol Int. 2005;75:213-216.

Prange W, Erbersdobler A, Hammerer P, et al. High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in cystoprostatectomy specimens. Eur Urol. 2001;39(suppl 4):30-31.

Pritchett TR, Moreno J, Warner NE, et al. Unsuspected prostatic adenocarcinoma in patients who have undergone radical cystoprostatectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol. 1988;139:1214-1216.

Rocco B, de Cobelli O, Leon ME, et al. Sensitivity and detection rate of a 12-core trans-perineal prostate biopsy: preliminary report. Eur Urol. 2006;49:827-833.

Ward JF, Bartsch G, Sebo TJ, et al. Pathologic characterization of prostate cancers with a very low serum prostate specific antigen (0-2 ng/mL) incidental to cystoprostatectomy: is PSA a useful indicator of clinical significance? Urol Oncol. 2004;22:40-47.

Weizer AZ, Shah RB, Lee CT, et al. Evaluation of the prostate peripheral zone/capsule in patients undergoing radical cystoprostatectomy: defining risk with prostate capsule sparing cystectomy. Urol Oncol. 2007;25:460-464.

Winfield HN, Reddy PK, Lange PH. Coexisting adenocarcinoma of prostate in patients undergoing cystoprostatectomy for bladder cancer. Urology. 1987;30:100-101.

Winkler MH, Livni N, Mannion EM, et al. Characteristics of incidental prostatic adenocarcinoma in contemporary radical cystoprostatectomy specimens. BJU Int. 2007;99:554-558.

Androulakakis PA, Schneider HM, Jacobi GH, et al. Coincident vesical transitional cell carcinoma and prostatic carcinoma: clinical features and treatment. Br J Urol. 1986;58:153-156.

Konski A, Rubin P, DiSantangnese PA, et al. Simultaneous presentation of adenocarcinoma of prostate and transitional cell carcinoma of bladder. Urology. 1991;37:202-206.

Authors and Disclosures

Roberta Mazzucchelli, MD, PhD;1 Francesca Barbisan, MD;1 Marina Scarpelli, MD;1 Antonio Lopez-Beltran, MD,PhD;2 Theodorus H. van der Kwast, MD, PhD;3 Liang Cheng, MD;4 Rodolfo Montironi, MD, FRCPath 1

1 Section of Pathological Anatomy, Polytechnic University of the Marche Region, School of Medicine, United Hospitals, Ancona, Italy

2 Department of Pathology, Reina Sofia University Hospital and Faculty of Medicine, Cordoba, Spain

3 Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University Health Network and Mount Sinai Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

4 Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis

Reprint Address

Address reprint requests to Dr Montironi: Pathological Anatomy, Polytechnic University of the Marche Region, School of Medicine, United Hospitals, Via Conca 71, I−60126 Torrette, Ancona, Italy.

American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2009;131(2):279-283. © 2009 American Society for Clinical Pathology